WPBS Weekly: Inside the Stories

March 7, 2023

3/7/2023 | 29m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

OASAS Prevention, The Mess Studio, and Musician Scott Bravo with "A Stealthy Mess"

WPBS visits the Office of Addiction Services and Supports in Albany for an in-depth interview on the status of the overdose epidemic in New York State. And artists in Kingston can freely express themselves in a unique space - come with us as we venture inside The Mess Studio. Also, Central New York musician, Scott Bravo, shares his original acoustic music in our studios.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

WPBS Weekly: Inside the Stories is a local public television program presented by WPBS

WPBS Weekly: Inside the Stories

March 7, 2023

3/7/2023 | 29m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

WPBS visits the Office of Addiction Services and Supports in Albany for an in-depth interview on the status of the overdose epidemic in New York State. And artists in Kingston can freely express themselves in a unique space - come with us as we venture inside The Mess Studio. Also, Central New York musician, Scott Bravo, shares his original acoustic music in our studios.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch WPBS Weekly: Inside the Stories

WPBS Weekly: Inside the Stories is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- [Stephfond] Tonight on WPBS Weekly: Inside The Stories.

WPBS visits the Office of Addiction Services and Supports in Albany for an in-depth interview on the status of the overdose epidemic in New York State.

And artists in Kingston can freely express themselves in a unique space, come with us as we venture inside The Mess Studio.

Also, Central New York musician, Scott Bravo, shares a session in our own studios, you won't wanna miss his original acoustic music.

Your stories, your region, coming up right now on WPBS Weekly: Inside The Stories.

(lively music) - [Presenter] WPBS Weekly: Inside The Stories is brought to you by the Watertown Oswego Small Business Development Center, Carthage Savings, the J.M.

McDonald Foundation, and the Dr. D. Susan Badenhausen Legacy Fund of the Northern New York Community Foundation.

Additional funding from the New York State Education Department.

- Good evening, everyone.

Thank you for watching WPBS Weekly: Inside The Stories, I'm Stephfond Brunson.

We kick off tonight with further discussion on one of the most challenging issues in America today, the overdose epidemic.

As part of WPBS's Overdose Epidemic Project funded by the New York State Education Department, we head to Albany to go inside the story of the crisis gripping our young people.

Our Joleene DesRosiers sat down with Chinazo Cunningham at the New York State Office of Addiction Services and Supports in Albany, and has more.

(gentle music) - Opioid addiction is a major crisis in America.

Since 2000, more than a million people in the US have died of overdoses, the majority due to opioids.

We are here at the New York State Office of Addiction and Supports speaking with Commissioner Chinazo Cunningham about the crisis, and specifically, how we can prevent addiction and use to begin with.

So thank you so much for having us, we appreciate your time.

- Thank you for having me.

- Yeah Very important topic.

And I wanna start with a basic question so everyone at home understands, what are opioids, where do they come from?

- So opioids are narcotics.

They are things that you've heard about like morphine, codeine, heroin.

Opioids also exist in the human body naturally but can be taken externally too.

So people are prescribed opioids typically for severe pain.

And people can also get opioids really through the drug market through heroin and now fentanyl as well.

So fentanyl is in heroin, it can be in cocaine it can be in counterfeit pills.

And that's a change that we've really seen in the last several years.

So 10 years ago, there was really no fentanyl in the drug supply, and now there's a tremendous amount of fentanyl in the drug supply.

- You were talking to me about something else that is found in our heroin and cocaine.

What is that, and what's the harm?

- Right, so we're seeing increased amount of xylazine in the drug supply.

So this is something that's relatively recent.

Xylazine is a tranquilizer, a sedative that's used in veterinary medicine, so not among human beings.

And so it's shown up in the drug market, unclear why or how, but it certainly is also dangerous.

And so because it's a sedative, it also causes slowing down of breathing and stopping of breathing.

So both an opioid and a sedative like xylazine together is a particularly dangerous combination that can really cause somebody to stop breathing.

- How long have we seen this?

- So there've been cycles.

So a few years ago, we saw this in Puerto Rico, some xylazine use, and then it kind of went away.

And then really it's only been in the last year or so that we've seen more and more xylazine in the drug market here, at least in New York.

- So we're here to talk about prevention, but I wanna talk about harm reduction first.

What is harm reduction, and how does it serve those who use?

- Yes, so harm reduction is a practical set of strategies and a philosophical approach that recognize that people use substances or drugs, and the goal is really to reduce the negative consequences or harms associated with substance use.

So harm reduction is not new, it's been around for decades and it's embraced in a lot of other countries.

In the United States, we started to embrace harm reduction around the HIV epidemic.

And so syringe services program, syringe exchange sort of came into play so that people, if they did use drugs, they didn't get HIV 'cause they used clean syringes.

And so that's been around for decades.

But now with the overdose epidemic, what we see is a more and more embracing of harm reduction.

So the focus is on reducing harm, keeping people alive, so that if people are going to use substances, and people have used substances in this world for hundreds of years, that people can use safely so that they don't die.

And really the goal is to help people become more and more healthy depending on where they are in their continuum of their substance use.

- Talk to me about what that looks like.

I know there's fentanyl strips, what else?

- Right, so syringes and needles certainly was kind of the first harm reduction supply.

More and more now, we have naloxone also known as Narcan, which can save people if they're overdosing so that they don't die.

We now have fentanyl test strips so that if people are going to use drugs, they can check to see whether fentanyl is in their drug and then they can change their behaviors accordingly.

We also have drug checking machines.

This is something we're supporting here, the state, so that people can check to see if xylazine or fentanyl or other substances are in their drug supply.

In addition, it's really also an approach in addition to the materials and the supplies, and so things like meeting people where they are, going out to places that don't have brick-and-mortar drug treatment programs and providing services there, doing outreach, linking people to services.

So it's really about meeting people where they are sort of both in their drug use and also physically and geographically, and really trying to have accessible services that are easily available with no barrier so that when people are ready, that the services there and ready and they can access them at the same day.

- So you have the mobile units, you have the harm reduction pieces, how do you make folks at home understand there's a stigma attached?

Are we helping them use the drug?

Talk to me about how that's not the case.

And again reiterating, until they're ready, it gets them at a place until they're ready.

- Right.

So again, harm reduction is not new and there's been a lot of research on harm reduction.

And the research across the world has shown that harm reduction strategies do not encourage drug use, they do not increase drug use.

But those harm reduction strategies keep people alive, they lead to less HIV and hepatitis C infection, people are more likely to link into to care and into treatment with harm reduction strategies.

So we know it's effective, and we know that it doesn't lead to more people using drugs or using drugs in a more dangerous way.

- Recently there were big monetary settlements with CVS and Walgreens pharmacies in which they agreed to pay more than $10 billion over 10 to 15 years to several states in regards to lawsuits brought against them alleging their roles in the opioid crisis.

New York is slated to receive about 458 million.

How will that money be allocated in New York?

- Right, so we have, by statute, an opioid settlement fund advisory board.

And so this advisory board was chosen by elected officials, the Governor and others.

So this board was convened in June of last year, and has met over 10 times since then.

The board comes out with formal recommendations, and so they submitted their formal recommendations to the state on November 1st last year.

And then the state takes those recommendations and moves them forward.

So our advisory board came up with a list of areas where they thought these dollars should be used to support.

The number one priority on that list was harm reduction.

- What are your biggest challenges when it comes to fulfilling your mission to improve the lives of New Yorkers by leading a premier system of addiction services through prevention, treatment and recovery.

- The biggest challenge honestly that we have is stigma.

The stigma that is involved with addiction in general, and then also with its treatment.

So growing up in this country, we all saw messages that said, just say no to drugs, and this is your brain on drugs, messages that made it seem as if people had, if they just had willpower, if they were just strong enough they could overcome their addiction.

And we know that's not true, we know that addiction is a medical condition.

And so we really have to change the narrative, we have to educate people about what addiction is and what effective treatments are.

Because there is effective treatment but people are not getting to it, and I think stigma is the biggest reason, the biggest barrier as to why people don't sort of identify as having addiction and then seek services that are lifesaving.

- Do you work with doctors to try to get them to prescribe other forms of pain management other than opioids?

And has changing those doctors' mindsets been a challenge?

- Yeah, so over the last several years, I think there's been a clear recognition that a lot of the overdoses that were happening were really in people who were prescribed medications.

And so the prescription opioids were the things that were driving the overdose.

When that was clear, there were major shifts in guidelines about prescribing opioids.

And so now federal guidelines really recommend that doctors do not use opioids long-term to treat pain, and instead use non-medication, so physical therapy, acupuncture, exercise, stretching, and then if they do use medications, to not use opioids.

So I think we've seen really big changes in how doctors really approach pain management.

And there have been some issues.

So I think, initially maybe the pendulum swung too far and nobody was getting opioids.

I think part of that led people to the black market and to heroin.

And so I think the conversation is now shifting to say, look, there's some pain that requires opioids, most of it doesn't, but we really need to work together for long-term solutions.

And for the vast majority of people, that does not include opioids.

- So when it comes to pain management then, can you speak to or do you know what other drugs they may prescribe?

- Right, so there's drugs that many people take like Tylenol or Motrin or Advil, and these class of medications are pretty effective in reducing inflammation and reducing pain.

And so I think it's really thinking about all the potential options, of which there's a menu of options for pain, but really saving opioids for the last option.

And this gets back to also the opioid manufacturers, that they were really pushing opioids years ago and that is why they were found culpable, and why we have the opioid settlement funds across the country.

- Well, thank you so very much for your time.

We truly appreciate it.

- Thank you so much.

- Moving into Canada now, we share an art studio that's changing how creatives express themselves.

The Mess Studio in Kingston, Ontario, is a diverse community where everyone is welcome.

Here, relationships and community are built through art.

(gentle music) (lively music) - [Gail] The concept of The Mess Studio started in 2009 when Sandra Dodds and fellow artist, Mechele te Brake, were having a discussion about the impact that a space to create art and build healthy relationships would have in the Kingston area.

That conversation sparked the humble beginnings of The Mess Studio.

They have gone from having three or four people gathered around a table, to now seeing more than 100 people creating art every week in Gill Hall, St. Andrew's Church, in Kingston.

- When Mechele and I first sat around the table at Martha's, we would dream about The Big Mess.

And when we landed here at St. Andrew's nine years ago, this has become The Big Mess.

We are in the basement, it's a very large spot.

St. Andrew's has been so gracious in allowing us to paint and make it into an art studio, change all of the bulbs into a photography grade, clear, clean light.

- [Gail] The large bright space in downtown Kingston is a place where people from different backgrounds, lifestyles and social experiences gather three days a week to create art, engage in conversation, and share lunch.

- I do believe that we were created to be creative.

And when that is stifled, I think we've lost a part of ourselves.

So getting back in touch with that, we do it in all kinds of different ways.

Some people cook, some people decorate their home.

But here, just allowing people the space and providing the equipment, the materials, the paint, it just allows them to get back to a place of health.

It is healthy for all of us to do something outside of ourselves, and it's a way of giving back.

- I grew up thinking either you're born an artist, you can actually produce something that's worth going up on the wall, or you can't.

But art is like music, you may be gifted musically but you still have to practice hours and hours a day, and art skills develop with practice.

The biggest thing I've learned is not everything has to be a work of art.

The process and the satisfaction of the creation is enough, and time spent with people is enough.

- [Gail] Regardless of artistic talent or experience, The Mess believes making art and engaging with community makes you healthier.

Instead of providing formal lessons.

they encourage everyone to openly express themselves through their artwork.

From painting to pottery, there is something for everyone at The Mess.

- We have an amazing group of artists, very diverse.

We're inclusive, so we have perhaps people that are actually doing art professionally come in.

We have people that, again, haven't done art since they were in public school.

We have the person that's just walking by on the street and sees our sign and says, "I'm gonna go and check that out."

So I feel like we have art, something for everyone, the art on the walls is indicative of that.

You can find abstract, you can find realism, representational.

I am really excited about the diversity of this community because it makes us unique.

- As you spend more time here, you grow to be part of the community, you're putting down roots.

And I'm just the type of person that enjoys being with people.

And I thought it would be really nice to get into a milieu of people who have needs and basically to try to establish a rapport with all kinds of people.

- [Gail] With a mandate to engage and empower people to become more active in their community, The Mess operates without volunteers.

Everyone is a community member and those that help are active community members.

People come in and they conserve lunch, help clean up, and sort paints and supplies.

- As we become more comfortable with one another, people take on roles.

And that does create a feeling of home and a feeling of acceptance and of value.

Every one of us wants to be seen and heard and valued.

- The best thing I find is the people that come here, Sandi and everybody else.

And you can do whatever you'd like to do, pottery, painting.

You can just come in and relax and talk to people and have tea if you want.

I feel welcomed, and I'm accepted here.

- [Gail] It is that sense of community and belonging that has made The Mess Studio a special place.

The Mess welcomes anyone into the studio anytime they're open to walk around, view the art, have a coffee, and talk to the artists.

The art is meant to be shared because that is what community does.

- If you came in and didn't know anything about The Mess, you would say, "Wow, what brought together this diverse community of people to be operating such as family and really caring about one another?"

And it's art, and it's the fact that we strive to walk beside each other.

Nobody's trying to go ahead or say I'm this and you're that.

We are community and we love one another.

- [Gail] For WPBS Weekly, I'm Gail Paquette.

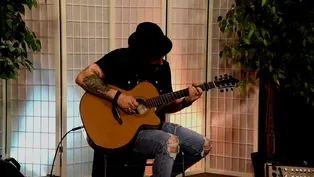

- Every musical artist we bring into the studio is unique in their own right.

And our next featured guest is no different.

He is Scott Bravo, an instrumental acoustic guitarist, born and raised in Central New York.

A New York City resident today, this powerful musician shares his sloth style of playing.

Here he is with his original song, A Stealthy Mess.

(upbeat drum music) - I'm Scott Bravo, I live in New York City, and I'm a musician.

I am from Syracuse, I'm from everywhere but I spent my early years Syracuse area, and I ended up in New York City.

Why not?

Why not go to New York City?

I have a picture of me when I was three years old, the first time I saw a guitar.

Just the look on my face holding it, I just knew there was something about this thing.

And then throughout my life I'd picked up guitars that friends had had and I just knew that I felt something when I held a guitar.

And when I was 15 I got my first guitar, and that was all I did, that was it.

I really wasn't good at anything else.

I wasn't really great at sports, I wasn't so great at school, but I just loved playing guitar.

And I never took lessons, and I learned by, I had books, Metallica, Guns N' Roses scale books, and I would just play along with the records.

And the more I played, the more I could hear what different chords were, so I could listen to other songs and sort of pick through them and figure it out.

And then I joined a cover band when I was probably 17, and I had to sneak out and go play in bars at night every now and again so that was fun.

So finger pickers use all their fingers, flat pickers use just a pick.

And I use a pick and one finger, three fingers, like a sloth.

So that's sort of my own, that's why I don't sound like anybody else.

I don't sound like a finger picker, I don't sound like a flat picker, I've got sort of my own thing.

Because I can't do either and get the sounds I want.

And the sloth is sort of like my spirit animal.

They sleep all the time, they're just chill.

I'm a pretty chill guy, I think.

So sloth style.

So the song I'm gonna play now, A Stealthy Mess, one of my favorite guitar players, Pierre Bensusan, writes in a very, not rhythm-free, but very loose style.

So I wanted to write a song like him, and I was looking for a title and one of my friends mentioned the term, I was a stealthy mess.

And I thought, that's awesome, you just named my song.

So it works like that sometimes.

You write a song and you don't know what it's gonna be called, or I have a title and I don't know what the song is yet.

So it doesn't always happen like ABC, and this is one of those times.

I'm Scott Bravo, and this song is called A Stealthy Mess.

(lively guitar music) (upbeat music) - That does it for us this Tuesday evening.

Join us next week for a fresh look Inside The Stories.

Meet Gary and Justin VanRiper, the father-son author team behind the children's book series, The Adirondack Kids.

And visit the Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center in Northeastern Adirondacks.

Stories and cultural pieces from the Mohawk and various tribes are showcased.

Also, who is the 1000 Islands Wanderer, and what is he doing?

We'll introduce you to Mitch Beattie, a Canadian filmmaker determined to show you the islands in a different light.

Meantime, we want to hear from you.

If you or someone in your community has something meaningful, historic, inspirational, or educational to share, please email us at wpbsweekly@wpbstv.org, and let's share it with the region.

That's it for now, everyone, we'll see you again next week.

Goodnight.

(bouncy music) - [Presenter] WPBS Weekly: Inside The Stories is brought to you by the Watertown Oswego Small Business Development Center, a free resource offering confidential business advice for those interested in starting or expanding their small business.

Serving Jefferson, Lewis and Oswego Counties since 1986.

Online at watertown.nysbdc.org.

Carthage Savings has been here for generations, donating time and resources to this community.

They're proud to support WPBS TV.

Online at carthagesavings.com.

Carthage Savings, mortgage solutions since 1888.

Additional funding provided by the J.M.

McDonald Foundation, the Dr. D. Susan Badenhausen Legacy Fund of the Northern New York Community Foundation, and the New York State Education Department.

(lively guitar music) (gentle music)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

WPBS Weekly: Inside the Stories is a local public television program presented by WPBS